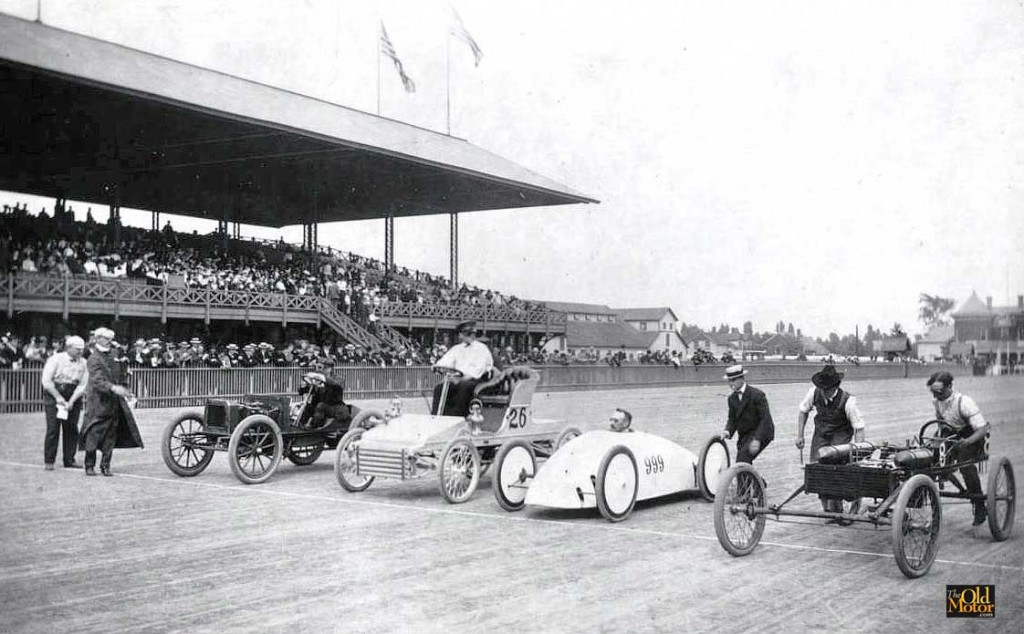

Below is the full story of the Baker Electric Torpedo land speed record vehicles culled from numerous sources. I have tried to make this the most complete source of information on these visionary vehicles available. Before the first airplane ever flew in 1903, there was the dream of being the fastest person in the world. And, Walter C. Baker was obsessed with that dream. His "Electric Torpedo" was supposedly the first vehicle to exceed 100 mph, in 1902. It was followed by two smaller vehicles, like "999" in the photo below, called the "Torpedo Kids". Baker was known "Bad Luck Baker" because of all the crashes he was involved him. And, I believe that is our protagonist, Mr. Baker, in car "999", that looks like it was beamed down from a spacecraft. Its shape was a pioneering example of what came to be known as aerodynamics. OK, buckle up!

THE BAKER ELECTRICS: A BRIEF

HISTORY Baker founded the American Ball Bearing Company in 1895 to produce axles for horse drawn carriages as well as for electric motors and steering knuckles. He then teamed up with his brother-in-law, a Mr. Dorn, to form the Baker Motor Vehicle Company (BMVC) in Cleveland, Ohio in 1898, after building an electrical vehicle of their own in 1897.

BMVC's first car to market, in 1900, was a two-seater, the

optimistically

named "Imperial

Runabout". Priced at $850 it weighed 550 pounds, had a

10 cell battery, a rear axle bevel gear and Baker's

patented steering knuckle. In November 1900 it was shown in New York

at the nation's very first auto show,

where

some of these vehicles were also likely on display.

It was the first shaft-driven vehicle, and the first

battery-powered vehicle, to be publicly displayed. The

show attracted a number of notable

buyers, including Thomas Alva Edison, who purchased one as

his very first car.

Edison also designed the nickel-iron batteries used in some

later

Baker Electrics. These batteries had

extremely long lives

and

word is that some are still in use today. In 1901

the Runabout won a silver medal for it's performance at

Buffalo's Pan American

Exposition. To offset the range anxiety inherent in the electric vehicles of this era, BMVC began considering a local battery-charging infrastructure, but expansion into the production of electric trucks, police patrol wagons, and even bomb handlers, was not enough to fend off the surging popularity of the internal conbustion engine, especially after Cadillac introduced the first electric starter in 1912. Baker addressed these problems by constructing several recharging stations and hoped to have recharging stations at every major intersection in Cleveland, but only a handful were actually installed. Baker also reacted to the growing dominance of medium-priced gasoline cars by emphasing the elegance and expense of electric vehicles, going so far as to uinsg a Louis IV style on its car interiors and calling its vehicle "The Aristocrat of Motordom". In 1914 a French fashion designer was hired to make its decorating decisions. BMVC tried to outwit the gasoline automobile producers with mechanical innovations as well. In 1912, it purchased the patent rights to the "Entz engine" which used a gasoline generator to drive an electric motor. The R.M. Owen Company then began producing the Entz engine for its own vehicle, the Owen Magnetic, under Baker's license. (Jay Leno owns an Owen Magnetic too!) But, by 1915 BMVC needed a new product so it merged with another electic vehicle maker, the luxury market focused Rauch and Lang Carriage Company, one of the most prominent electric car manufactures in Cleveland, and began producing Owen Magnetics. However, the Entz engine proved difficult to manufacture and by 1918 the Owen Magnetic was the third most expensive car in the country. During World War I the new merger also produced electric lift trucks. It ceased the manufacture of electric cars in mid-1919, and was reorganized as the The Baker Raulang Company and thereafter focused on buiding electric lift trucks, along with car bodies for other companies which continued until 1943. In 1954 it became a subsidiary of The Otis Elevator Company and has carried on in one form or another until the present day.

Now, on to the show!

THE BAKER TORPEDOES

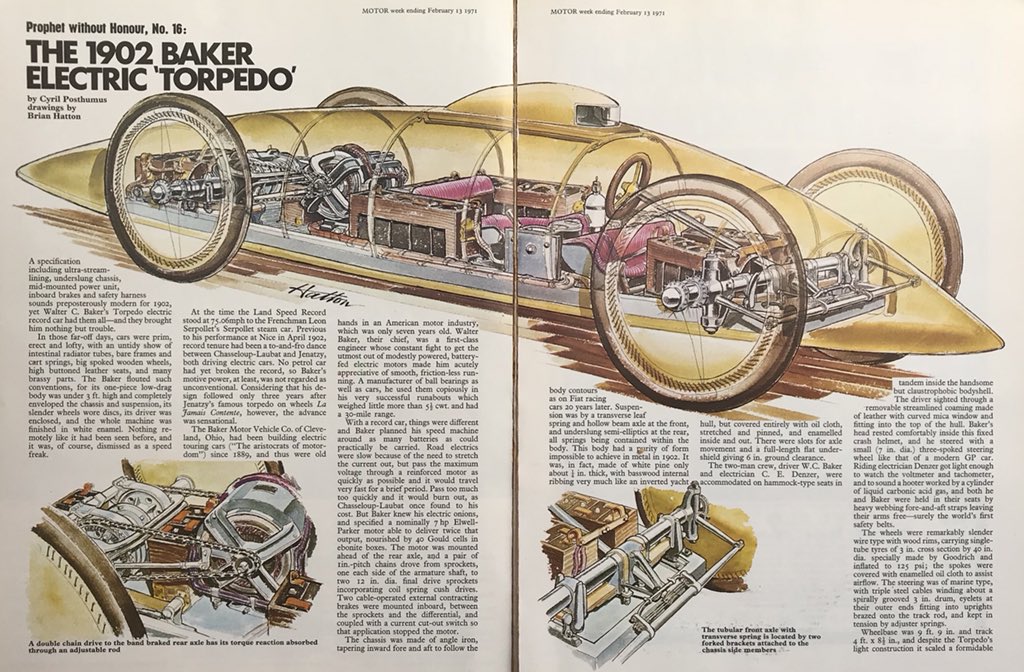

The Torpedo's highly aerodynamic body

was made of lightweight white pine covered with

oilcloth coated with an enamel-based paint.

Most importantly, the Torpedo's driver and passenger

were strapped in

place

with innovative four-inch canvas shoulder harnesses,

believed to be the first application of seat belts. Their heads poked

up into an

isinglass bubble surrounded by a cork crashpad.

The windows were only about 2 inches tall.

Unfortunately, the Topedo, seen before the event, above, left, was built for straightaways and had little steering ability (ironic given Baker's patent for a steering kunckle) and almost no suspension. When it hit the exposed tracks at Lincoln Ave. it "leaped" from the street surface and the steering went limp. Denzer tried to brake, but a ton and a half of wood, iron, batteries and two men, going faster than any motorists had ever gone before, was beyond control. The Torpedo veered to the right, then sharply left and rolled onto its right side, as its wooden wheels disintegrated, before plunging into the horrified crowd, striking several and killing one, Andrew Fetherston, instantly. At least five were hospitalized, some with battery acid burns. But, Baker's safety harness likely protected him and Denzer from serious injury, although Baker and Denzer were immediately arrested on the scene for manslaughter. The aftermath of the crash is seen above, right. When it was ultimately determined that the victims had crossed a safety barrier, the charges were dropped. However, the crash disqualified Baker and Denzer's achievement that day from being entered into the WLSR record book.

Undaunted, Baker decided to re-build the Torpedo and raced it several times on closed circuits in 1902 and 1903. He also constructed the two Torpedo Kids, with production motors from actuall BMVC passenger cars. In October 1902, in Cleveland and Detroit, he drove one Kid in speed demonstrations, supposedly at record speeds, but the actual figures remain uncertain. Then, in August 1903, Baker entered both Kids in a special event for electric cars at the Glenville circuit near Cleveland. His co-driver, a Mr. Chisholm, started in the pole position and was doing fine untail he was sideswiped and lost his steering. Chisholm crashed and knocked down four spectators but no one was really hurt. But, Baker, who was driving the second Kid, decided to pull the plug on his electric car racing dream and stop running into people. In 1920, at age 52, Baker had retired from active involvement in his businesses to pursue his hobbies of ham radio and flying. When he was 72, in 1940 he received the Distinguished Service Citation Award from the Automobile Hall of Fame and the main BMVC building still stands and was renovated as recently as 2007 and added to the National Registry of Historic Places. Despite his unfortunate moniker, Walter C. Baker was a true visionary in every sense. Fascination with the Baker Electric Torpdoes continues and in 2017 a replica, using modern components, of 999 was built. Here's a 2010 video of Jay Leno comparing modern EVs with a 1909 Baker.

Wouldn't Mr. Baker's life make a great movie? Who should play "Bad Luck Baker"? If you enjoyed this site, please be sure to visit our page about the 1955-57 Gaylord Gladiator, the "most expensive car in the world". If any information here is incorrect, or you have some to share, please e-mail me.

|